But I started listening to these recordings, and I started thinking about ballads, and jazz.

I've written before about the American Century in music, that great artistic flowering that grew out of the blues, and generated such a profusion of genius in such a range of musical styles.

And many people have written, correctly, about exploitation of black music, black culture, and especially black musicians and composers. Ta-Nehisi Coates has written a brilliant article on the case for reparations -- the argument that

America has prospered off the backs of black people, not just in wealth, but “Our policies, our social safety net, the way we think about housing in this country, social security, the GI Bill — these things would not have been possible unless we made certain compromises with white supremacists, to be perfectly honest about that.”Sometimes left out of this argument is yet another black creation that may be America's most profound export, and one of its most financially rewarding -- rock and roll. Which is a white expropriation of a black art form.

The economics of American music have mostly flowed one way, from black creators into white pockets. And yes, I know about the empires built by P. Diddy and Jay-Z and Russell Simmons, and more power to them, but they're still the exception, and historically they're a blip. Joseph Smith, who had some success as Sonny Knight in the 50s, as a rhythm and blues performer, later wrote a scathing and underrated novel about the white-dominated music business of his era, The Day the Music Died.

But that. too, is only part of the story. The greatness of American music is in its impurity, its mongrel nature, its ability to reach out, gather in, and blend. Economically, everything may have flowed one way, but musically, there was cross-pollination. While Elvis was covering the songs of Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup and Roy Brown, and recording the songs of Otis Blackwell, streetcorner groups from Harlem were finding new ways of interpreting standards like "Sunday Kind of Love" and "Over the Rainbow" and "Glory of Love." Earlier, Louis Armstrong had created a timeless classic from Carmen Lombardo's "Sweethearts on Parade." Jazz connoisseurs have chuckled indulgently over Armstrong's fondness for Guy Lombardo's orchestra, but Armstrong heard something in the Lombardo brothers that the rest of us didn't.

Much has been written about the Great American Songbook, and the songs which have become such a part of the soundtrack of our lives, and certainly those songs stand on their own. But the European tradition of composers like Gershwin was immeasurably enriched by their discovery and appreciation of jazz.

Perhaps the first European composer to fully appreciate this was the Czech Antonin Dvorak, who said:

"In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music. They are pathétic, tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn, religious, bold, merry, gay or what you will. It is music that suits itself to any mood or purpose. There is nothing in the whole range of composition that cannot be supplied with themes from this source. The American musician understands these tunes and they move sentiment in him."I'd read Dvorak's famous pronouncement before, but I hadn't seen some of the unsurprising responses to it by conservatorians of the day:

Dr. Dvorak is probably unacquainted with what has already been accomplished in the higher forms of music by composers in America. In my estimation, it is a preposterous idea to say that in future American music will rest upon such an alien foundation as the melodies of a yet largely undeveloped race.

Quaint as those songs may be, it is a poor fountain from which the young American composer could sip his inspirations.And, to be fair, those weren't the only responses.

To the Editor of the Herald: It gives me pleasure to indorse [endorse] the ideas advanced by Antonin Dvorak. I have long felt that Americans have not appreciated the beauty and originality of our native melodies. We possess a mine of folk-song, such as few, if any nation have, and it would be well if our composers should employ those themes in writing their works. In this way we should develop a really American school of music, and find our public would gladly encourage the movement. As it is the treatment of a simple melody which evinces true musicianship, why should not our composers select such airs, instead of going abroad for their ideas?George Gershwin was probably the first, and probably the greatest composer of his age to be profoundly influenced by jazz. Still, at least until Porgy and Bess, his songs were originally written for and sung by white singers, as were the songs of all the popular composers of the day, the ones writing what became the Great American Songbook.

But nothing lasts forever, or at least nothing lasts forever without changing. Shakespeare changes with each new generation, each new production, each new interpretation. And the songs of Gershwin and Kern and Porter and the rest might not have remained such an important part of American culture if they hadn't become part of the repertoire of black singers, who come from a different musical place, a different cultural awareness. Pop singers like Ethel Waters and Lena Horne and Nancy Wilson. Jazz singers like Billie Holiday and Ella and Sarah, Carmen MacRae, DeeDee Bridgewater, Nnenna Freelon.

But I wonder if people have thought much about the impact of modern jazz on the Great American Songbook. The great jazz improvisers added a whole new dimension to these songs, and I believe, gave them new relevance. Even the Tony Martin or Jerry Vale fan, listening to Miles or Sonny or Phil Woods (or Billy Taylor or Marian McPartland or Errol Garner) go off into an improvisation, and wishing they'd come back to playing the melody -- yeah, even the squares knew that when a great modern jazz musician did play the head, he was bringing something new and strange and wonderful to that melody. The modern jazz players, creating a new music from deep in the black experience, incorporated the songs of European-American composers (and European composers like Debussy). They took, and they gave back. And that's American music.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits."The Way You Look Tonight" was written for Fred Astaire, and if a song is written for Fred Astaire, it's a good bet that it swings, and that it will be a natural for jazz musicians of any school. It's been recorded by Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, by Miles Davis and Dave Brubeck and Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson and Johnny Griffin and Herbie Hancock. And the song crossed another generational and cultural gap when it was adopted by the streetcorner harmonizers in the style that became known as doowop. Several groups recorded it, including the interracial foursome from Los Angeles, the Jaguars, who transformed it into something different, and something beautiful, in an era when harmony was king.

Interestingly, the beboppers, in mining the Great American Songbook, didn't stop with the Gershwins

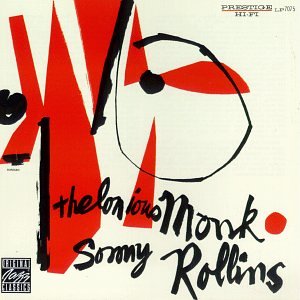

and Kerns and the other jazz-influenced composers. They recorded songs by composers who came out of an earlier tradition, who were really from the operetta era, like Sigmund Romberg and Victor Herbert. Vincent Youmans is really of that school, too, and the other two songs from this session are both by Youmans. But Rollins and Monk find gold in them, find the basis for improvisation and innovation and discovery. I can imagine Jerome Kern listening with wonder and admiration to what Monk and Rollins do with his song. It's harder to imagine Youmans having the same reaction.

Monk and Rollins are wonderful collaborators, and they work together by letting good fences make good neighbors. Each gives the other extensive solo space. There's not much in the way of duet voicing, or trading riffs. Tony Martin/Jerry Vale/square though I may be, I think my favorite part of the session is Sonny Rollins's lyrical and imaginative statement of the melody in "The Way You Look Tonight," which is enough to make anyone cry.

This session was first released on a 10-incher which saw Sonny Rollins get top billing. "More Than You Know" was also put onto the Sonny Rollins - Moving Out LP along with the tunes recorded in August with Kenny Dorham and Elmo Hope. "The Way You Look Tonight" and "I Want to Be Happy" were grouped with the tunes from Monk's September trio session on an eponymous album in 1957, which was then rereleased as Work in 1959. This was Monk's swan song on Prestige, as he moved over to Riverside.

No comments:

Post a Comment